I’ve let this concept slide for a while, so it’s time to get back on track. I’m going to try to shift my focus to include more bloggers, small websites, and positions I disagree with from now on.

—

“Batman and the Problem of Constituent Power” – David Graeber (guest post at De Dicto 10/28/2012)

I’m a fan of David Graeber as a critic of capitalism; as a critic of film and pop culture, however, I’m much more ambivalent. This is his take on The Dark Knight Rises (and superheroes in general) vis-a-vis the Occupy movement. The main problem with the essay is that it starts out with cliched and at times incorrect or overstated claims about the superhero genre. To put it bluntly, Graeber comes across as someone who is not well-read enough in the existing criticism of superheroes to be writing about them. Because of this, I’m guessing this essay will lose (or enrage) most comic fans and critics early on as he seems to be appropriating something without studying it thoroughly, and doing so in order to make a point about one specific film that he could have made without such overgeneralizations. That said, the concluding arguments about how The Dark Knight Rises ends are worth pushing through to the end and considering.

—

“The Myth of Meritocracy” – Christopher Powell (The Practical Theorist 11/14/2012)

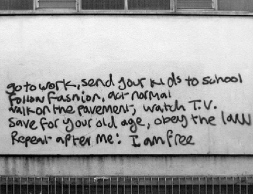

Powell is one of those relatively rare, practicing academics whose public writing is written clearly, with a minimum of jargon, and without arrogance. He often deals with difficult theory but doesn’t try to make concepts harder than they need to be. I’m a big fan of that. In this essay he lays out the structural inequalities that affect student academic success. Upon reading it, the points he makes seem so obvious that you tend to just nod your head like you knew this all along, which you probably did even if you never articulated it clearly.

You must be logged in to post a comment.