The simple divisions of civilized versus primitive or civilization versus wilderness are rarely actually simple.

To reiterate what I said in the first part of this post . . .

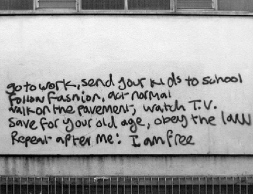

Dystopian fiction is often concerned with what can easily be presented as simple dualisms: freedom/restriction, happiness/misery, individual/collective, logic/passion, reason/emotion, civilization/wilderness, and so on. When I have taught dystopian works, I use these to give students an anchor and rubric for their reading and thinking about the texts. However, these pairs can also become blinders for analysis of such works, allowing critics, including authors of the works themselves, to over-simplify the complexity of ideas therein into a simple “this or that” option that neglects so many questions of politics, philosophy, and definition.

To my mind, the most glaring examples of this over-simplification are in the spacially-oriented conception of civilization versus wilderness and, by extension, the more complex idea of civilized versus primitive. In the two posts that will follow, I’m going to take a look at how these concepts are flattened, simplified, and misrepresented in the two defining texts of dystopian literature: Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.

Part 2: Huxley’s Brave New World and the Not-so-primitive “Savage”

Like Zamyatin (who he claimed to have not read), Huxley builds his dystopian world off of the examples of H.G. Wells’s utopian fiction. Likewise, he situates in a world of what seem to be mutually exclusive binary categories. And again, a central question is the distinction between the civilized (manifested in the World State, its logic of stability, and its citizens) and the primitive (ostensibly all that is necessarily eliminated from the World State).

Within this context of exclusion as definition, the spacial location of the primitive is the Reservation at Malpais (the bulk of which is seen in Chapters 7 and 8). However, the primitive and uncivilized is also usually read as embodied in the character of John “the Savage,” a young man born (in the old-fashioned way) on the Reservation of parents from the World State. He becomes the primary protagonist of the novel’s second half when he is brought to civilization (the World State’s London), and the central conflicts in the book are illustrated most extensively through his dialogue with World Controller Mustapha Mond (in Chapters 16 and 17).

You must be logged in to post a comment.